When developing a mobile app, it’s easy to focus on what’s visible – the general design identity, the user onboarding process, the backend, even marketing. However, one thing I learned over the years is that some of the best features you can have in an application are invisible, and as such, seldom discussed. It’s not until later that their need becomes apparent.

After a tweet on the subject, I realized there’s not a lot of talk about certain mobile app features that are invisible to most users but still necessary. And that’s what this article is about.

Your app needs server-supplied feature flags to toggle new capabilities

Suppose you want to introduce a new feature to your app, and this feature is somehow dependent on the server. Let’s call this feature ZOINK.

You need to follow a sequence of steps that allow your new feature to be supported. It goes something like this:

- Implement ZOINK in the server, and deploy a new version of the server

- Deploy a new version of the client app that supports ZOINK

That’s simple enough. However, suppose you’re not sure whether ZOINK will be a good feature; you may want to do a slower rollout, or perform some A/B testing for a while. While you can usually do that with app releases, it means your build version is now linked to whether you want someone to get ZOINK on their app or not. Releasing normal bug fixes while doing a staggered app rollout is more complicated.

To complicate matters more, suppose the version of the server supporting ZOINK requires a different payload of some kind, making it actually incompatible with older versions of your app. You might need a more complicated set of steps – including intermediary versions of the app and the server, and potential app forced updates – to get your feature out to the public without leading to crashes or version mismatches. Or suppose you want to disable ZOINK right after rollout; you now need to do it all again, going through the motion of doing new releases for both the client and the server.

The gist of it is, it gets complicated.

The solution to this is something called feature flags. This has been discussed at length before by other people (including by Martin Fowler and Justin Baker), so I won’t have to get into detail, but it basically means that the server should tell the client what features it supports.

This is done by either a simple JSON payload, or a request of some other kind during app initialization. Many services already offer this as a feature, including Unity Analytics’ Remote Settings and Firebase’s Remote Config, for example.

When this is implemented, what your app does is check this list of supported features, and then perform business logic accordingly. It does mean that your app will ship with dual implementations for some piece of functionality, but more importantly, it means you can toggle this feature on and off at will. This is great even if you only have one target server/environment running at a time. The value for that flag can also be based on a user dimension; for example, if you only want 10% of your users to have that feature enabled, you can check against some unique client id and return a weighted result. More importantly, overall, it means a lot less coordination between server and client releases, and assures breaking feature releases are painless.

Of course, feature flags can also be used for other parameters, such as toggling API server rates, minimum/maximum values for some range, or controlling any other piece of business logic, all in near real time and with no app updates required.

It might sound like a fancy feature, but I’ve seen breaking server changes between different releases, and believe me, it’s not pretty. It’s only now that I realize a lot of problems I’ve had in the past would have been easily avoided with feature flags. Apps can great benefit from feature flags; ignore them at your own peril.

Your app needs a way to block old versions and force updates

Considering the responses to my original tweet, this position might be a bit controversial, but my stance is that every mobile app should, from day 1, have some way to block users from running old versions of the app if necessary. This would preferably be done with a 2-step process where users receive a warning about version deprecation first, and then are completely locked out of the app after a certain amount of time has passed.

While the idea of locking a user out of an app they possess might frighten some, consider the reasons for it.

Suppose you want to migrate users of your app to a new backend API. You keep the old API in place, deploy a new version of it, and then deploy an update to your app that targets this new API. But the old API must still be available, since the app client won’t immediately be updated on everybody’s devices. However, it’s likely your old API will have to be active forever, since there’s always a fraction of users that never update their apps; you can’t just deactivate the old API, since it will break the app for those users without a warning. You risk having to maintain two separate server backends for your application from that point on.

Or suppose your application has a security flaw that you want to patch. You issue a new version, but again, many users will not update their application for a while. Is it ok to let them keep an insecure version of their app?

In an ideal world, users of your app would migrate over time. But that’s not the reality. The reality is that some users just turn off app auto-updates, or are never using an unmetered connection (such as home wifi) where auto-updates are triggered by iOS or Android. They will not care about updates unless being asked to.

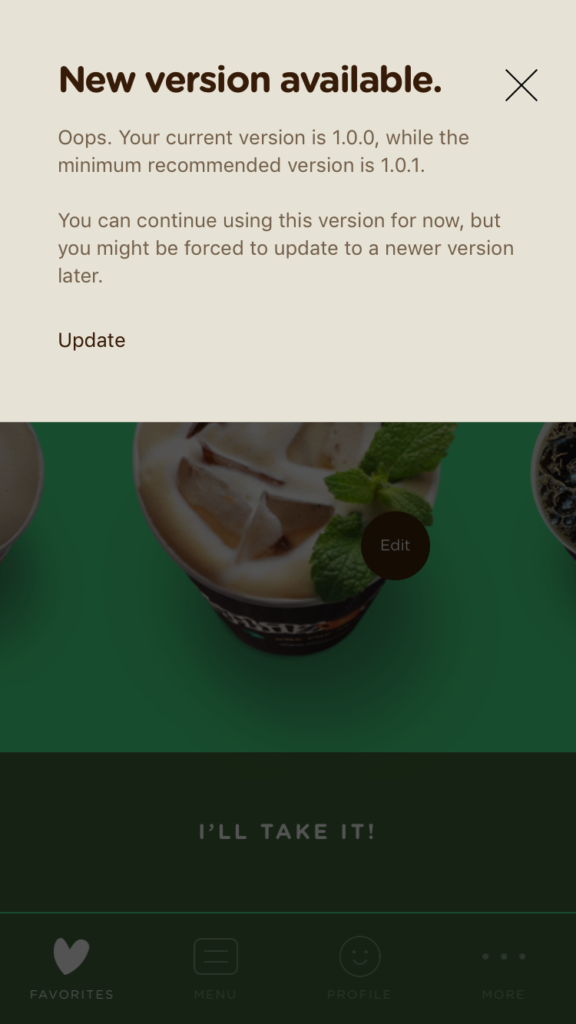

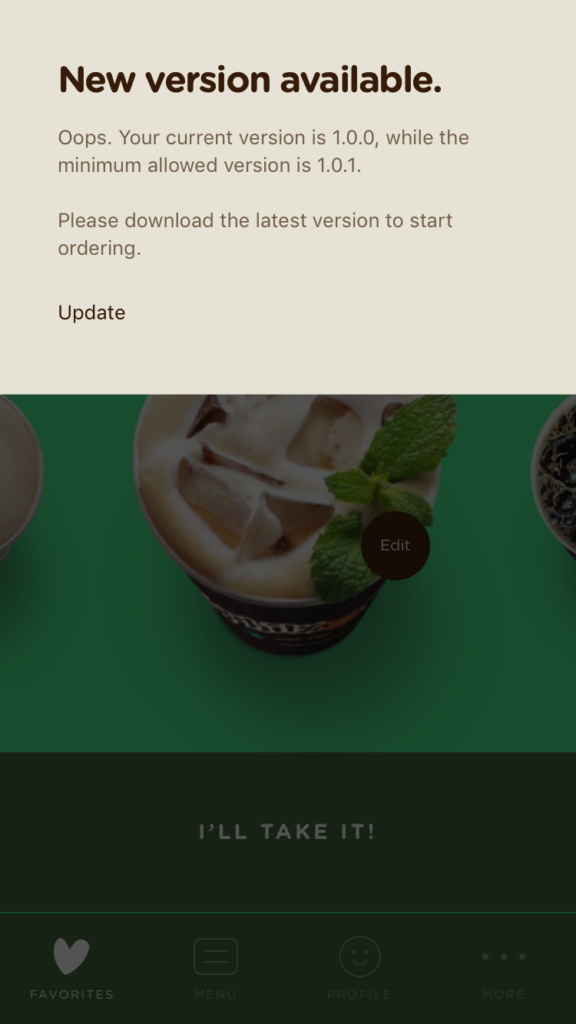

So in my mind, the best solution here is a 2-step approach. First, when you know you are going to deprecate a version of your app, you show a warning to users during the app’s startup, letting them know that the version they’re using will stop working soon, and giving them a way to update. Then you let them continue using the app.

The second step is actually blocking the version at a later time. When the user runs the app, they get a message that states their current app version is deprecated and blocked, and again, giving them an option to update and no way to continue using the app.

From a technical perspective, there are different ways to implement this. My current go-to is simply having a static JSON file that gets loaded during the app’s start process. It would look something like this:

{

"versions": {

"blockBelow": "1.0.13",

"warnBelow": "1.0.13"

}

}

Then, once the app loads that file, it checks whether the current app version is older than the version in blockBelow, and if so, blocks the user; and, if older than warnBelow, the user is just given a warning about deprecation and future blocking.

There are other ways to implement this feature. There are certainly libraries and services that can do that for you, although the implementation is so simple that I’d rather have if done from scratch (and as such, fully customized to what I actually need, with no dependencies, etc). Or, depending on what you’re using as a service, you might not need or want a static JSON file somewhere; you can do that part of your server payload, or use feature flags as mentioned above.

While this feature’s use may seem cruel, remember that this is not something that should be done on every app update. This is a last-resort for when updates are necessary because of a server resource change, or security risks. It should be performed very rarely, and only after a long enough period where you wait until the vast majority of users have updated their apps normally. Ideally, a very low percentage of your users would ever see an update request of any type.

But, believe me, when you are two years into an application’s life cycle, and you still see users on version 1.0.0, you will certainly wish you had this feature implemented since the very first release.

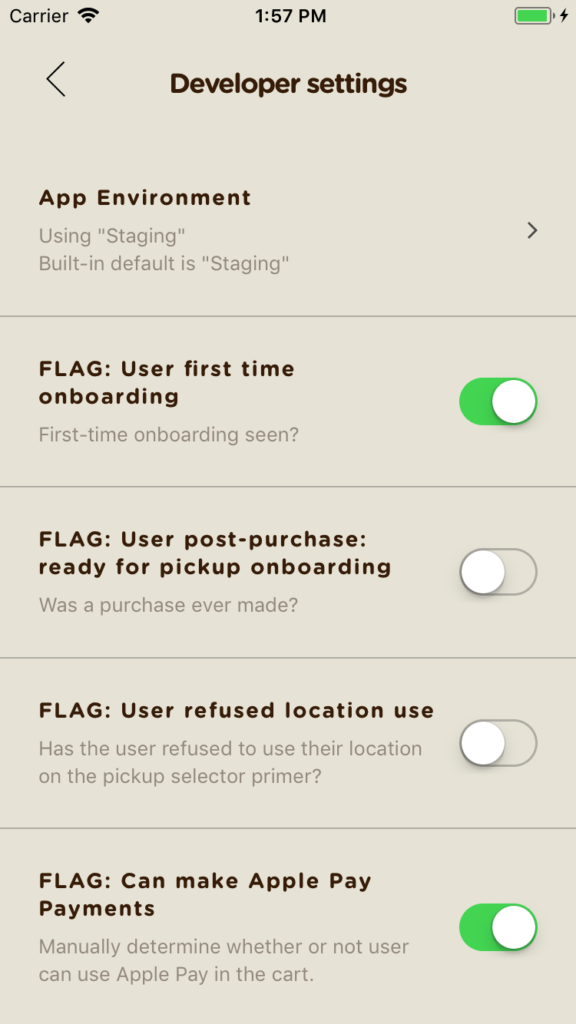

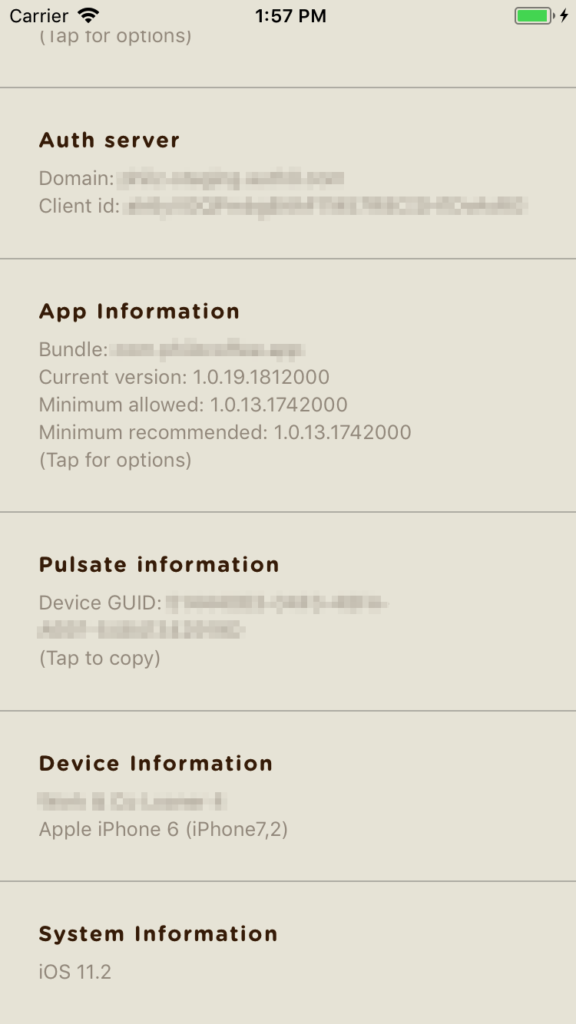

Your app needs a hidden dev menu with development/test-specific info, flags, and buttons

Frequently, when testing an app, you need to take a look under the hood. This means doing anything ranging from mundane tasks such as checking an app’s version number, to looking at what is the key being used to access a certain service or some session-specific id. You might also need a way to tweak things, such as turning a test flag on or off, changing some variable, or triggering some sort of special action.

Features like this are easily done if you have a developer menu inside your app. A developer menu should be a hidden section of your app that features any sort of information or functionality that developers (or testers) might need to properly test an application, even if it’s not running directly from out of your development IDE.

Normally, I use a hidden menu not just to present app status information, but also to allow tinkering with some parameters. For example, on my latest project, we have a flag that allows tinkering with the app’s assumed location, to enable test buttons on the normal user interface, or to make the app always assume the user is a “new” user and present the onboarding flow.

While these flags are easily implemented as hardcoded constant flags, exposing these as toggles via a dev menu allows anyone testing the application to use them without the need for a new build. Features such as these have the potential of making your QA team’s work much more efficient.

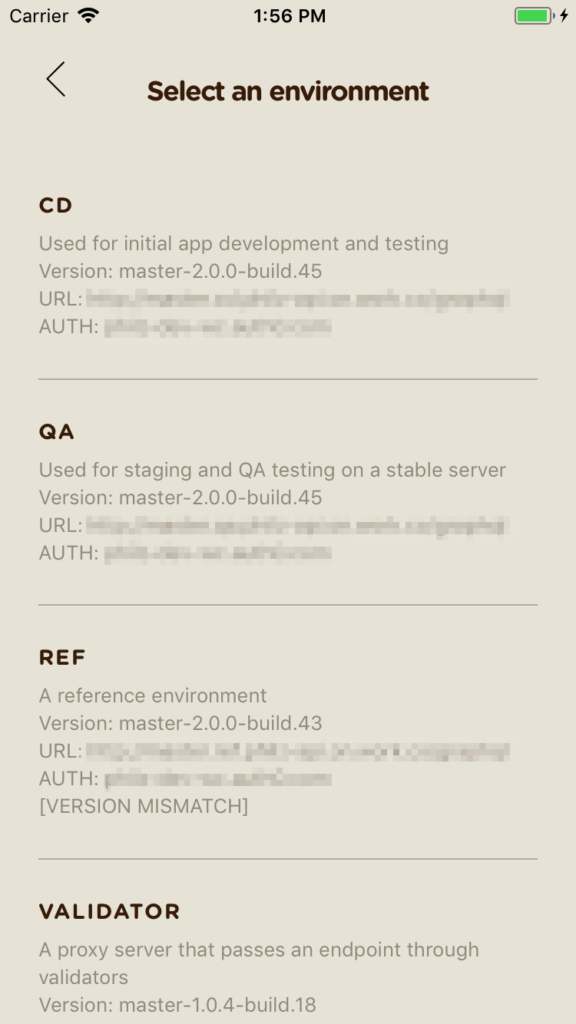

Your app needs a way to target different environments

Finally, this is a feature that is really useful but often forgotten. When you’re dealing with different server environments (say, staging and production), you need to give your application the ability to target any environment you want.

It’s common to solve this problem by using things like environment vars. You could, for example, set the url of a service with a URL_ENDPOINT env var and have that consumed during your application’s build process somehow. Or you could group sets of variables into .env files and load them during build. Or, in case of Android native apps, you could have different product flavors during build.

This, however, is just half the solution. Ideally, instead, you should have just one single build (which is easier to distribute for testers) but make the environment changeable. My current approach is having a complete list of environments inside the app, with all the settings they might need such as URLs, keys, and some behavior flags. These are exposed via an internal list, accessible via a secret gesture or a hidden button, or better yet, via the hidden developer menu.

Then, during build, a variable simply sets the target environment id (say, “production” or “staging”) that should be used as default.

None of the topics covered here are mind boggling, I’m sure, but I’m still surprised at how overlooked they normally are. It took me a while, but today, I not only consider them important, but things any healthy mobile app should take advantage of from day 1.