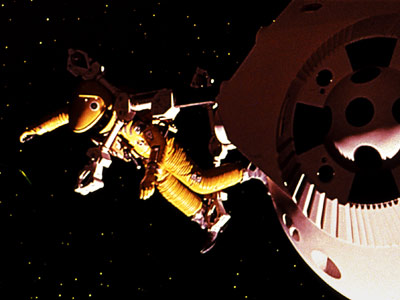

The 26th edition of the weekend-long competition Ludum Dare is just wrapping up. The theme this time around was “Minimalism”, and as I had decided to create something for the Oculus Rift, I decided to re-create a scene of the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey: the scene where astronaut David Bowman has to rescue Dr. Frank Poole.

In a way, this wasn’t an idea I wanted to go with at first – while the space theme (and the feelings the movie bring as a whole) can be seen as related to minimalism, there’s no real game on it. I normally use Ludum Dare to learn, however, so I thought it was a good enough reason to use the movie as a context in the absence of brighter game-like ideas.

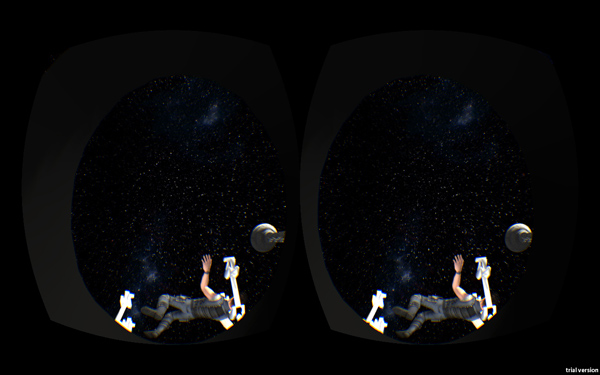

The result is called 2001: A Space Oculus. It’s available for Windows and Mac, and requires the Oculus Rift to be played. Source code is also available.

In this “game”, you have to rescue an astronaut that has been floating in space by taking him to the front of the space ship. I also wanted to try a simulator with a difficult control – QWOP-style – so controlling the pod is admittedly hard.

It was certainly an interesting learning experience. While I’ve been toying with Unity for the past few months, I hadn’t created a full game-like experience yet, so there was much I had to research.

The good

Using Unity

Using Unity is certainly interesting. In a way, it’s very easy to get a game running with very little. It reminds me of the days of using the Flash IDE: you could just plop some content on the stage, add just a little bit of scripting on top of it, and get it doing all kinds of crazy things right away. I wonder if that kind of easiness served as a guide to the Unity developers when creating their IDE.

Because of that, starting the game was a breeze. I opened the Tuscany demo (available as part of the Oculus SDK), changed a few assets, and was running around in a space-floating Tuscany set in no time. It went from that, adding one little thing at a time.

Doing the jam

I decided to do a more relaxed entry this time – as part of the slightly-less-restricted jam, rather than following the compo rules. This allowed me to use third-party content on my entry, which was necessary since I wanted to reproduce a famous movie set (fan-made props were likely to exist as 3d model somewhere else).

The bad

Using Unity

While it’s certainly a great tool (and my game-like thing wouldn’t be possible at all without it), there’s a catch to it, and maybe it’s a more personal one.

Over the past few years, I’ve evolved as a Flash developer into someone who would not only use a different IDE for code writing, but also a much better managed project structure that was entirely based off pure ActionScript code (with resource loading or embedding as needed). As a result, none of my projects were based off the Flash IDE, and I would never run it anymore unless I needed to export some vector art. I felt that kind of workflow much better in the long run, and much easier to work around in complex situations.

Hence why going back to the stage-drive approach of Unity made me feel… dirty. Going back to hacking stuff on the stage and adding scripting to it.

I’m trying not to be judgmental, and of course I’m not a proper Unity developer, so maybe it’s just my temporary impression. But while getting things started was easy, getting things to a point where I was happy with where harder than I thought. I’d constantly run into seemingly bizarre engine problems that forced me to deviate from the easy path for a while and implement some script meant to patch over the problems, or look for a hack online.

In the end I had to import, write, or edit several editor scripts meant to do little things to my meshes in an attempt to solve some of the shortcomings I’d run into. While the availability of the editor script is a strong positive feature for the platform – you can tweak the editor to your heart’s content, and do some pretty complex content manipulating with it – it also means that I spent a lot more time fiddling with content fixing and creating editor features rather than proper game content creation. I wonder how complex the editors of seasoned Unity developers look like; they probably had tons of additional commands to solve common issues they run into.

I also had trouble changing much of the Oculus Rift support scripts. While the Tuscany demo works very well if you want to get a 3d first person shooter going, it can be hard to wrap your head around it if you want a more unorthodox control. For example, I initially wanted the pod to be able to rotate around in space in all axis – for true space flying. However, I had a lot of trouble fixing the code so you could rotate around and, say, be upside-down, and in the end opted to freeze the user’s X and Z rotation. This is mostly due to my lack of proper understanding of quaternions and Euler angles, I suppose. Given time, instead of reusing existing code that has been put together in a way that “just works”, it would have been better to start something fresh with a proper understanding of the Rift’s SDK’s internals (and Unity’s 3d space coordinates).

Using third-party content that’s not ready for a game

Again, my project wouldn’t be possible without third-party content, so I don’t mean to imply that’s a bad thing. The problem with using content found elsewhere is that while they may look right, they may not perform the way you wanted it to.

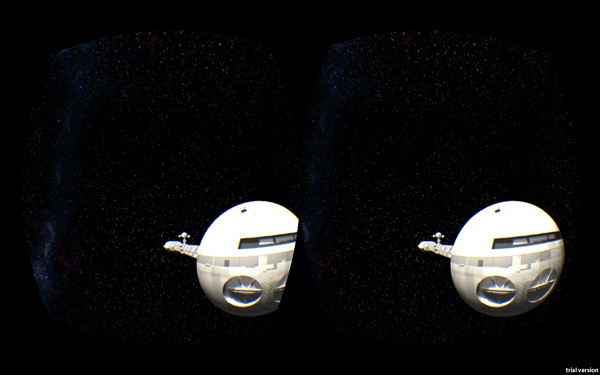

I had plenty of problems with the spaceship Discovery’s meshes – they were all using weird origin points. I had to write a script to reverse the normals of a few select meshes. The internal unit scale was all goofy, and it had some hidden meshes that exploded or moved around when imported.

The rescue pod had no interior. Parts of the arms where attached to the hull, even though they were a separate mesh (which took me down a spiral of trying to fix it in Blender, only to realize Blender didn’t support the original mesh smoothing groups, forcing me to export the model as an OBJ from within Unity using yet another script, then spending hours getting the arms split).

The list goes on.

It’s certainly amazing that fans find the time to model movie content as well as they did. I’m very grateful for the fact that I could be flying around a ship from a movie in 3d space in no time – that was a delight. But one has to consider the problems with adapting content such as this. Given time, I’d have spent a good amount of time tweaking the models in something like Blender, and getting it in a state the Unity platform would be happy with. As it is, I’m surprised it worked.

Conclusion

Overall, this was again a great learning experience. I’m happy my “game” has a final objective this time around too (as hard as it is, given the physics and the complex control). And while I don’t think it’s super fun as a game, hopefully more people will enjoy floating around in space and simulating that scene from the movie. I was certainly overjoyed. There’s some things you can only experience with the Oculus Rift.

Finally, I ended up not using usfxr, the sound generator library for Unity that I had created with Ludum Dare in mind. In the end, though, Ludum Dare is about experimenting and having fun, so I don’t feel bad about changing my goals halfway through the competition. I’m sure I’ll be using it in the future, however.

Open the pod bay doors, Zeh.